Ross

and Co. of Dublin were one of the most important makers of campaign furniture

in the Victorian era and justifiably, their name still stands out as a leader

in their field, today.

With

the rapid growth of the British Empire in the

19th century, came the increased movement of administrators,

colonists and of course the Army and Navy. It was not uncommon for an officer

to have what would now be considered a ridiculous amount of luggage. This is

perhaps best explained by a diary entry dated 1813 by Lieutenant – Colonel

William Tomkinson who noted why he equipped himself with 600 lbs of personal

baggage while on duty in Spain during the Peninsular war: ‘[My equipment] may

appear a large fit-out for a person going on service, but experience taught us

that campaign after campaign was not to be got through without the things I

have stated; and the more an officer makes himself comfortable, the better will

he do his duty, as well as secure his own health, and the comfort of those

belonging to him. It does not follow, that because we attempt the best in every

situation that we cannot face the worst. The poorer the country the greater

must be your baggage, from the length of time you are obliged to march without

obtaining a fresh supply.’

James

Ross Murphy and Patrick Murphy capitalized on the demand for portable furniture

that accompanied this increased movement of people with the formation of their

company E. Ross on Ellis Quay. Although examples of domestic furniture by Ross

are known the vast majority of their output was designed to quickly fold or

pack down for ease of travel.

The

company’s exact start date is unknown but the first record of Ross is 1821 when

they are listed in the directories as being located at 6 Ellis Quay. They

remained on the quay throughout their history although their address is listed

in the Dublin Directories at various combinations of the numbers between 5 to

11 and they are known to have also later had a factory at 35 Tighe Street (now named Benburb Street).

These two locations were of course ideally located for the many officers

stationed at Collins Barracks and this no doubt was a benefit to the business;

a fact also picked up on by John Ireland, their neighbour and an Army Clothier,

who was located at 11 Ellis Quay in 1850.

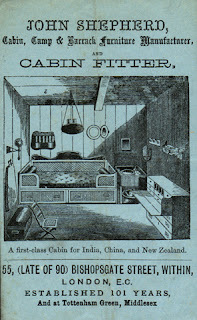

Ross

stand out from the many other campaign furniture makers of the period for a

number of reasons but perhaps the most important is their originality in

design. As can be seen from the adverts of the London makers of the day, such as Hill &

Millard, J W Allen and Day & Son they were all making fairly similar

campaign pieces. Their adverts would typically show a two part chest of

drawers, a washstand, folding bed and a Douro

pattern chair. There would be the odd item that was specific to a particular

maker but generally by the mid 19th century there were standard

pieces that most officers would require and which they could easily find from a

number of makers. Apart from their most basic chest of drawers, which followed

the traditional design, most items manufactured by Ross differed greatly to

that by other makers. A number of their chests would have a clever, folding

superstructure or an unusual combination of drawers, their washstands wouldn’t

have the normal brass standards adopted by the other makers but have turned

columns and their Easy Chairs would put comfort at a premium.

Much

of Ross’s work can be considered typical of the William IV and Victorian

periods in its use of the fashionable design features of the day. This would of

course have given their cabinet making greater appeal than that which was

purely utilitarian; an important factor to their customers who would mostly

have been well heeled gentleman officers with an eye for the stylish. It also

means that much of it is not obviously made for campaign until close

inspection. A good example of this is the Desk Chair below, that breaks

down into eight pieces for travel.

The

majority of campaign furniture was commissioned or retailed as individual

pieces but Ross very cleverly gave the option of buying a suite of furniture.

Such a suite would have a combination of a short set of Dining Chairs, an Easy

Chair, a Couch, a Center Table and a Chiffonier or Sideboard which broke down

to become the packing case. On the inside door of the cabinet furniture would

be a label, giving packing instructions. The packing case cabinets were often

adorned with carved decoration and moulding, which again was unusual for

campaign furniture that mostly considered flat surfaces and square edges to be

a pre-requisite. However, when it came to packing the cabinet, the moulding

would be removed and the carved show wood protected with a bolt on panel so no

sacrifice was made for the added decoration.

Perhaps

the most famous such suite is that made for Captain Simner of the 76th

Regiment and his wife, Francis Mary Bolton, as a wedding present on March the

27th, 1863. It was made from walnut taken from the family estate at

Bective, in Ireland and

travelled with the Captain and his wife to Madras, Burma

and Secunderabad over a 12 year period. They may well have considered it their

best wedding present, as it must have given great comfort in the very different

climate of the Far East. Ross’s concessions to

embellishment with the carving probably also gave a reminder of the Europe that they had left behind and so a feeling of a

little luxury in a harder environment.

We

are fortunate that Ross labeled most of their work with either a painted

stencil, or small ivory or brass plaque, giving their current address at Ellis

Quay. That which is not labeled was probably from a suite, where other items

would have the Ross mark. However it is usually relatively easy to recognize

Ross campaign furniture from its other traits. The use of walnut was common for

Ross, perhaps because they recognized its revival in popularity under the

Victorians, which again, would give an added selling point. Yet it was

untypical of most campaign furniture makers who generally preferred mahogany or

teak.

Ross’s

numbering, for ease of assembly, of the individual parts that make up a piece

of their furniture is also unique. Most campaign furniture makers used a simple

system, often using Roman numerals but always starting, naturally, with the

number one. Furniture by Ross is often given a two digit number or sometimes a

letter and number depending on the item and Roman numerals are not noted as

having been used. An example of such numbering is the set of four Balloon Back

Chairs, illustrated, where the numbers range from 62 and 63 on the first chair

to 70 and 71 on the second, 74 and 75 on the third and 92 and 93 on the fourth.

Although at first this seemingly random system of numbering doesn’t seem to

make sense it was probably logical for a factory that may have been making

several pieces of the same item of furniture at the same time. Added to this

Ross were probably selling their wares to members of the same regiments and

their numbering system may well have saved future confusion amongst brother

officers.

Ross

prospered through out the 19th century and by 1864 their reputation

was sealed by the approval of H.R.H. the Prince of Wales. By 1882 even the Army

were recommending them, something only done on occasion. The Report of the Kabul

Committee on Equipment (Calcutta) stated ‘….

the committee now consider it to be necessary for the comfort of an officer,

that he should have a bed, and they find that the pattern…made by Ross of Dublin is the most

suitable. It weighs under 20lbs.

The

success Ross and Co. of Dublin enjoyed throughout the 19th century

can be put down to a number of factors, the most obvious being that they were

very good cabinet makers. This quality of work coupled with their ingenuity of

design, which was quite distinctive from their contemporaries, and attention to

the popular styles of the day proved a winning combination. However, Ross also

had other factors working in their favour to create a strong customer base. Not

only were a large percentage of the British Army’s officers Irish but Ross were

clever enough to position themselves close to one of the biggest barracks in

Europe. The barracks were garrisoned by an Army that had spread itself across

the world and whose mostly landed officers could afford the best, wished to

travel in style and to have all the comforts of home when they arrived at their

destination.

By

1909 there is no listing for Ross in the directories and their last address of

8,9 & 10 Ellis Quay is listed as vacant, surrounded by tenements. Their

demise is due to the same factors that affected other campaign makers, which

put simply is that they were right for their time and their time was over. The

world and how war was conducted had changed significantly by the beginning of

the 20th century. The Boers, with their speed of movement and good

use of the ambush had taught the British Army a sharp lesson. Arnold-Forster,

the Secretary of State for War perhaps recognized that things had to change

when in 1903 he said ‘The British Army is a social institution prepared for

every emergency except that of war.’

Domestic use had also tailed off, there weren’t as many colonists as in

past generations and those that were heading off to make a new life knew that

their destination was now far better set up to furnish them than in their

ancestor’s days. The emergence of the motorcar also meant people could travel

far quicker and so did not need to take as much with them for the comfort of a

long journey. Although there was still a demand for both military and civilian

travel furniture the cake had become much smaller. Added to this Ross probably

suffered from the same effect that many independent retailers also do today,

the popularity of the supermarket. The end of the 19th century saw

the spectacular rise of The Army and Navy Store, a shop where everything could

be bought from a travelling shaving brush to a tent. Whether you were looking

to buy your groceries or a billiard table The Army and Navy Store could ship it

to you in most parts of the world.

There

is still much to be learnt about Ross of Dublin and it is a regret that there

are inconsistencies in their directory listings and so few records of the

company other than their furniture that survive. The discovery of a trade

catalogue would shed more light on their full range of goods and offer other

invaluable information. However, they have left a passion amongst collectors

for their camp equipage, much of which travelled the globe when it was first

made and is still doing so as it is eagerly sort.

by Sean Clarke and Nicholas Brawer

This

article was first published in ‘Ireland’s

Antiques & Period Properties’ magazine, Vol. 1 No. 3,

Summer

/ Autumn 2004.